Home Away From Home: Clara Matonhodze Strode on Creating a Home In A Complex Racial System

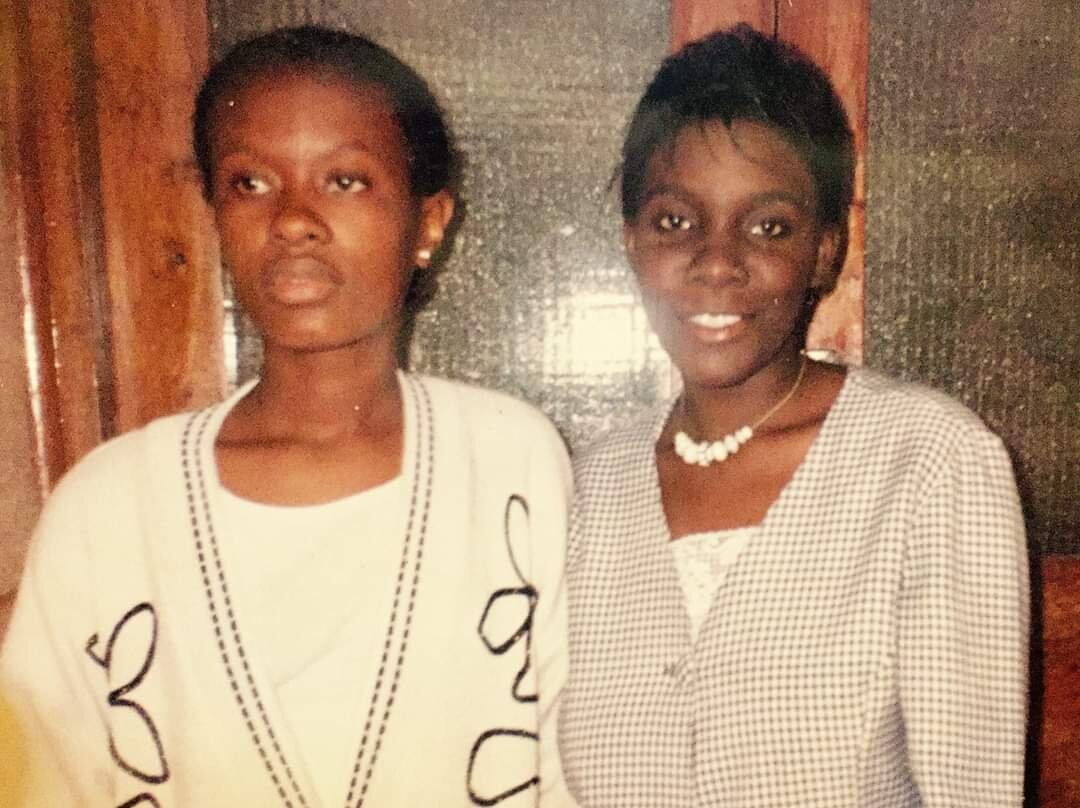

Written by Clara Matonhodze Strode. Photos provided.

As the writer and creator of "Home Away from Home" I would be remiss not to speak on what it’s like to create a home as an immigrant in a country rife with racism – deliberately practiced or unwittingly doled out; institutional or personal. As such, I decided I needed to explore my own coming to America story within a racial context.

Racism in America consumes me just as much as it consumes Black America. It is a never-ending topic of discussion. A constant source of worry, and dabbling into self-doubt – Is it me, or was that...? Sometimes it paralyzes me; it generates emotions in me that I had no idea I could feel. I have wished I didn't care; I have practiced blissful ignorance. Many a shameful time, I have turned a blind eye, creating physical and psychological stress that I am only now coming to terms with.

I fought with all my might to never play the "race card," often blaming myself for making mistakes within a system built to disadvantage me. Even as I write this, I recoil at the last sentence because deep down, I'm still prone to blame myself rather than point a racial finger. After years of living in America, I am well aware of the subtle microaggressions and outright hostility – it’s not a construct of my imagination. It runs through American life like a tsunami; sooner or later, it will consume you.

I'm Not Black, I'm African

I wasn't always like this. You could say that I thought like most of white America. I was oblivious to what was happening around me. Growing up in Zimbabwe, in southern Africa, racism was never an issue. Our prejudices centered around education, class, and tribalism. I never thought of myself or anyone I knew as Black. We were: Shona (tribe), Zimbabwean (Country), African (world geography) – in that order. At 18, I had spent a year living in a newly independent South Africa (where even the dogs were racist), and I survived without fear.

When I first came to America, a young 23-year-old, I was determined to stay above it all. In America, I found it peculiar that Black people are referred to as African American. In my opinion, someone like me, emigrating from Africa, would be African American. Descendants of slaves would be Black American because let's face it – they are American. A middle-class Black American has more in common with a middle-class white American than a middle-class Zimbabwean. Africans living in America are still deeply rooted in their African culture and traditions. In contrast, Black Americans' culture and traditions tend to be similar to those of Western civilization; they have cultivated and created their own unique culture.

Innocence Lost

My first experience with the American racial system was in the early 2000s. A recently arrived Immigrant, I was overflowing with excitement and inspired by the East Coast's cosmopolitan semblance. Philadelphia's South Street felt like an indulgent walk through the condemned Sodom and Gomorrah. Palmers Social Club was the spot we danced all night, went back the next day for more Montell Jordan, left at 5 a.m. with enough time to get to the apartment, dress, and head to the train station to head out to college in Camden. Rinse and repeat. Life was crazy good.

With that backdrop, I caught wind of the trial of New York police officers who, after three days of deliberation, were acquitted of killing an unarmed immigrant from Guinea, West Africa – Ahmadou Diallo. It baffled me. “American police officers kill innocent people?” I thought. "How did they not know he was African?”

The obvious answer is they didn't because he was Black. It's an answer I had to learn to understand.

You see, most Africans "recognize" each other. We recognize regional traits in physical appearance that others don't. This is not a scientific truth, but it's generally true from my experience. I might not be able to say this person is from Ghana, but I might generally "know" they are from the west, east, or the south of Africa.

Likewise, most Africans like to think they can easily differentiate between the physical traits of Black Americans and African Americans. I thought everyone had that same understanding. I learned from the Ahmadou Diallo case that in America, my being is reduced to a single component – Blackness. Black skin. It doesn't matter where I'm from, what I do, who I know, it matters that in America, life filters through a racial façade, first and foremost.

To create a home in America, I had to accept this fact. I am Black.

Evolving in Thought

This realization was unsettling and confusing to me, but I was determined not to let it affect me. “Black Americans needed to get over this.” This is how I used to think about racism. Africans got over colonialism. "It's not my fight,” I told myself. My family agreed. "You're above that," my dad said when I would start to talk about race during our phone conversations. "You're in the best country in the world," my mom reinforced. "How are others managing?" an uncle quizzed. "Yeah, I'm above that, and it's not my fight," I reaffirmed to myself. History backed me up.

“Most slaves that came to the Americas,” according to history writer Sarah Pruitt, “Came from two regions: Senegambia… today's Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau and Mali; and west-central Africa, the so-called ‘Slave Coast,’ which is now the West African nation of Ghana, as well as neighboring parts of the Windward Coast, now Ivory Coast.”

In my mind, I had no dog in this fight. I was even more removed from this fight about the legacy of slavery. I was from southern Africa, thousands of miles away from Bagamoyo, Elmira, Goree, Quidah, and any of the slave ports that facilitated the transportation of human cargo and created a genocide of the human spirit.

How wrong I was, as I would soon learn.

Now, to be clear, this is not a "dog on America" article. I have fallen deeply in love with America – warts, racism, public spitting, and all. I love it even more during this time because I believe at the end of the upheaval, America is one step closer to achieving its ideals of liberty and justice for all. And that's the beauty of this country – civic institutions that allow people to determine their destiny. They did it with the end of slavery, they did it with the end of Jim Crow, and they will do it again with Black Lives Matter. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, "Let us realize the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."

Painful as it might be for those who have to endure the length of the arc, solace lies in knowing future generations are the beneficiaries. That makes it easy to create home – knowing my children will fare much better than I when it comes to race relations.

The College Years

In college, I took an African American history class to understand more about the racial dynamics in America. I was introduced to the concept of "double consciousness" in W.E.B. Du Bois's The Souls of Black Folk:

Double consciousness is... this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity... to be both a Negro and an American without being cursed and spit upon.. without having the doors of opportunity closed roughly.

As the class went on, my existence in America slowly unfolded. Not as "double consciousness," but what I think of as a "quadruple consciousness." The tribe identity has been taken over by the color of my skin and morphed into gender and geographical identification. As a Black woman, I exist at the intersection of race and gender, and by crossing the Atlantic Ocean I exist at the intersection of culture and migration. Black; Woman; African; Immigrant.

I was never accepted by the white organizations on campus, often asking me to show up for cleaning rather than the planning. The Black organizations didn't fare any better – I regularly was accused of not being "African enough" because I didn't dress or do my hair as "Africans would," whatever that meant, and I still don't know.

Perhaps the most shocking was the realization that just like white America, Black America also looked at African immigrants with a hybrid of prejudice, disdain, discrimination, and suspicion. Sociologist Nancy Foner writes this about Liberians and Black Americans after studying their social dynamics, “Both Liberians and African Americans sought to distance themselves from each other—each, interestingly, claiming superiority over the other—and tensions arose over competition for jobs and housing.”

It was the same scenario in college.

I did much better with international organizations. I was accepted as a committee member and even managed to get a paper accepted at an academic conference. I found a home with global enthusiasts. I loved the multiculturalism of the International Student Union, and I made friends with white and Black Americans who liked to hang out with international students. There, I established friendships with people from all over the world; Saudi Arabia, Russia, Taiwan, Italy, India, and Nigeria; I even dated a Mauritanian. These surprise friendships have lasted to this day and taught me I could make a home by creating my own community of people who believed in multiculturalism. We were in America, after all.

Why bother about tribal politics that had not evolved for thousands of years? The magic was in everyone coming together, finding common ground to create deep and meaningful relationships.

Identity Politics

It is a ditzy world obsessed with the categorization of people and stereotypes. I'm guilty of it too. Back in Zimbabwe, as I was doing my goodbye tour before leaving for America, I visited an old professor I held in high esteem. He was a U.S. college alum. His comment stunned me, "You will get along better with whites than you will with Blacks because of your education," he said.

I came to expect relations with white America to be difficult because of this; I did not fall neatly into any of America's categories for people like me – which made it even harder for me to navigate the corporate world. I didn't do office politics well, and I preferred the quiet confines of my office to the endless laughter from jokes I didn't quite understand.

Once during a performance review, I was told people thought I was too direct and unfriendly. That I never accepted lunch dates. I could see that. I was also a single mother of twins in daycare, no childcare vouchers, dealing with an abusive ex, and making $40K/year. Going out for lunch or being chirpy was a luxury I could never afford. And that's pretty much how my work life went – a series of misfires with co-workers, but great relationships with clients who never wanted to deal with anyone but me. So I wondered, “Was it really me, or was it something else in that office lurking under the surface?”

I would go on to work at other organizations, and it felt like they were just checking boxes without bothering to understand them. The community wants an African celebration? Give it to them but don't fund it. Let it die by a thousand cuts. You want an office for diversity? Set up one but give it no power. They listen and shake their heads and go about their lives – and so it goes in America. Always playing the carrot and stick game without ever releasing the carrot.

My power came when I realized that the American Dream was not about working for somebody and seeking approval. It is about the opportunity to chart your own course and make your vision come to life, and that is a country where I want to create a home.

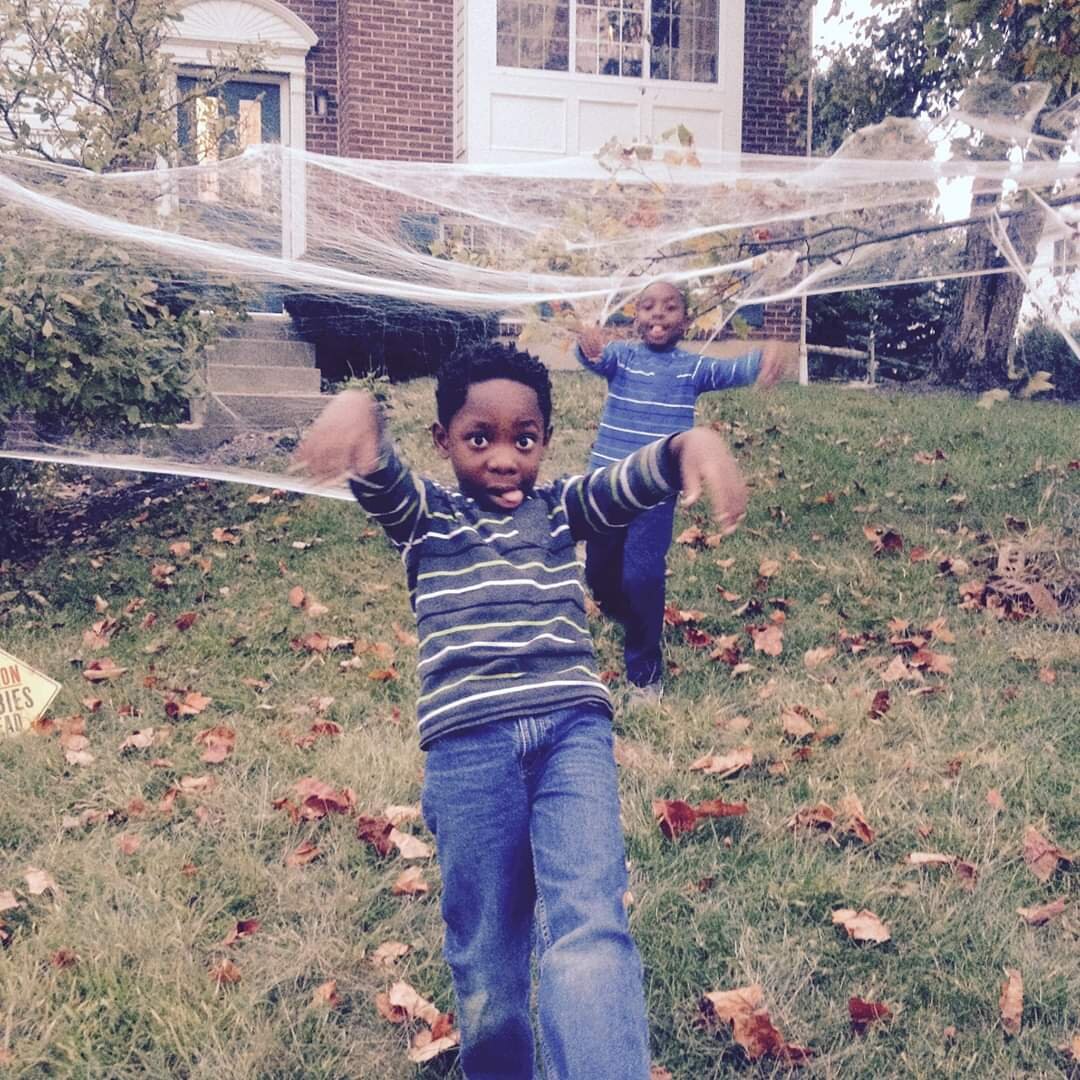

Raising Black Boys

My hardest struggle living in America as an immigrant is still unfolding – raising Black boys. When you take all these complexities and throw children in the mix, the formula gets more complicated. It comes with pain. Not just for me, but for the children I watch play happily in the cul-de-sac, oblivious to the hate around them.

We moved into our neighborhood when the boys were two years old. In our cul-de-sac lived a family with kids three years older than the boys. Those kids loved my boys. They would come over and spend a whole day at my house. As time moved on, the boys grew. Around the age of 7, one of the boys stole a kiss from the girl. I overheard a conversation that went something like this:

Little girl: Oh Bill, you can't kiss me!

Bill (giggling): Sorry...

Bill's brother: Why not?

Little girl: Because you would be my boyfriend! My Dad told me I can be friends with brown people, but I can't date them.

Me (out of curiosity): Can you tell me why?

Little girl: Because my mommy said brown boys can get me in trouble... I told them that wasn't true, but my dad said I will be put in prison.

That this family, whose kids would literally follow my boys around so they can play together, would tell their daughter this was a gut punch that leaves me bleeding to this day. At that time, I didn't do anything. Summer ended with them still playing together, winter came, and we all hibernated.

The following summer, the little girl and her brother were on our doorstep again. I overheard another conversation where this little girl told my boys that she was sad because they were all getting older. She wouldn't be able to play with the boys because her dad said to her that "teenage Black boys would land her in jail," so they couldn't play together as teenagers.

At this point, the mama bear in me came out. I went to their house intending to discuss this conversation with the parents. After about 10 minutes of knocking and ringing their doorbell and no one coming out despite them being home, it occurred to me that they were ignoring me.

I went home and wrote two letters. One said everything you can think of in terms of the racism they harbored. The other letter (which is the one I delivered) said something to the effect: “Our kids play together, it's a cul-de-sac, let's be friendly and get to know each other, come for dinner. If you don't want to, make sure your kids are not in the street when mine are playing. I am not having conversations with my kids about where and who they play with. Make sure your kids never come to my house again.”

They never came for dinner.

After that, they would smile at me in the driveway, wave, and I always gave them the stink face until they gave up. Their son and daughter never set foot in my house again.

And that about sums up raising Black boys in America. A painful exercise that makes me want to saran wrap the boys and put them in a bubble. Creating home with this fact is difficult, but I lean on my community of like-minded multiculturalists who want to see our children thrive and become good global citizens.

So yes, issues of race consume me now. Over the last 20 years, they have manifested themselves over and over again in my life. I'm no longer an ignorant denier of the adverse effects of racism. However, I have concluded that I can still create a home by seeking out like-minded people. I can't get rid of racists but I can carve an adequate space in my community where my family is safe, happy, and surrounded by those we love. And thank God Cincinnati has plenty of those communities.

Catch every chapter of “Home Away from Home” with Clara Matonhodze Strode.