Sitting with the Uncertainty: A Conversation with Dr. Ashley Solomon

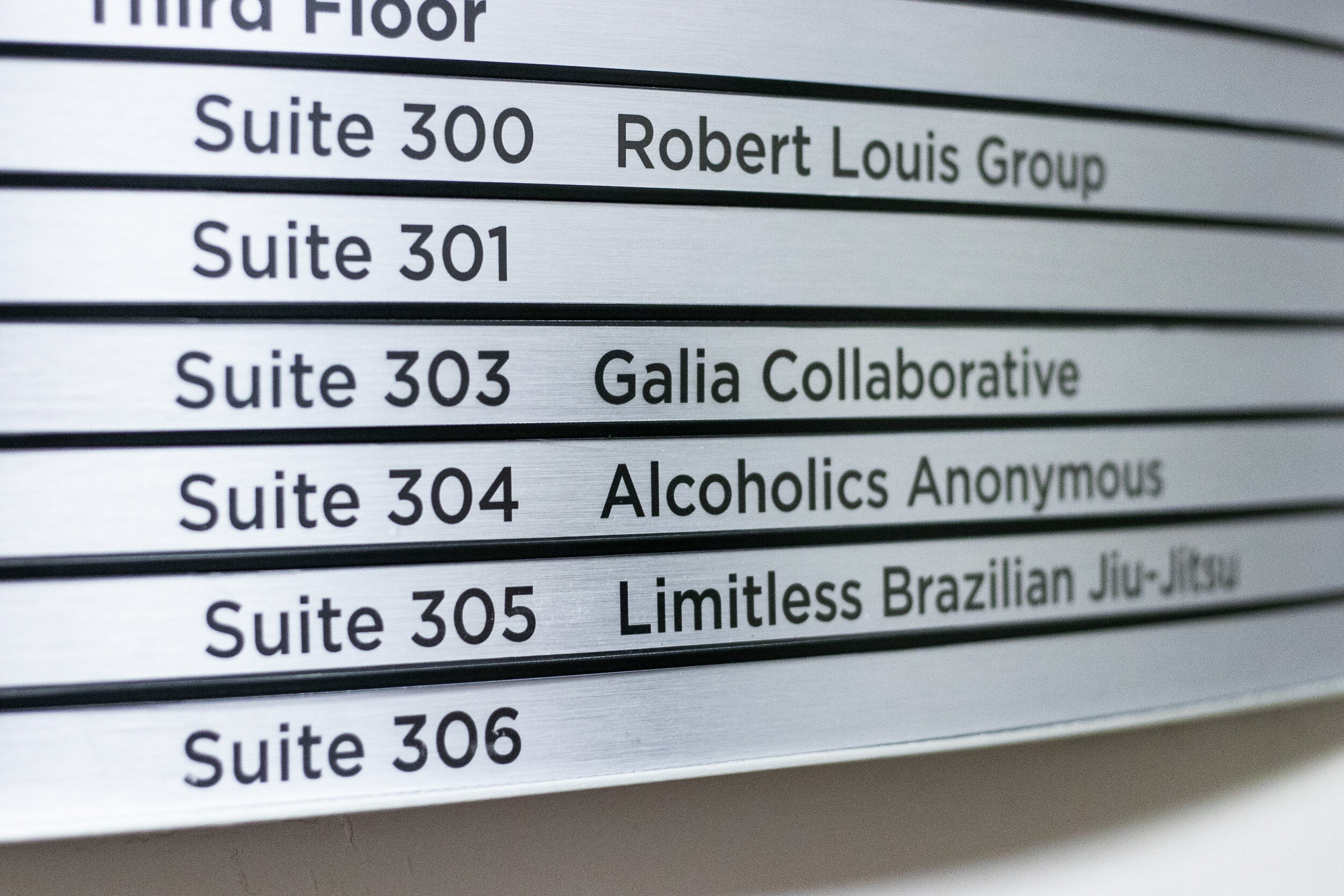

On a sunny, Friday April morning, I put on some makeup, brewed a pot of coffee, tidied up my kitchen table, and logged into WebEx for my first virtual, stay-at-home-order Women of Cincy interview with the effervescent founder of Galia Collaborative, Dr. Ashley Solomon. With its name meaning “her power” in Lithuanian, it comes as no surprise that Dr. Solomon’s therapy and coaching practice is founded on the principles of social justice and intersectional feminism, helping women develop their mental strength and overall well-being to embrace their power.

While the interview process looked a little different than usual, I quickly felt Ashley’s warmth and grace radiate from my laptop screen; the warm and fuzzy feeling that comes with good conversation has a way of pervading even the strangest of situations.

Interview by Kelsey Johnson. Photography by Chelsie Walter. Sponsored by Galia Collaborative.

Women of Cincy currently adheres to social distancing guidelines during all interviews.

To kick things off, why don’t you tell us about yourself?

I’m a licensed clinical psychologist; that's my foundation, professionally at least. I'm also a wife and mom to four young kids: My daughter is almost six months old now and then [my other children are] two, five, and seven.

My professional background is specialized in the treatment of eating disorders; that’s where my dissertation research and all my clinical administrative experience was. I went to grad school at Xavier, and did the doctoral program in clinical psychology there. I love that work. I did it for almost 10 years following graduate school, and I never ever thought I would stop doing that – well, I haven't really stopped doing that work.

Tell us about your work treating eating disorders.

I worked with patients who were severely struggling with symptoms. I loved doing this work for a lot of reasons. In outpatient treatment, people are struggling with different things, but it’s a more incremental change. I loved doing the higher levels of care where someone’s life is transformed over a shorter period of time because the transformation is super apparent. I also loved the intersection of medicine and psychology because there’s a strong medical component, and there's a strong psychological component [when it comes to treating eating disorders] too. That gave me the opportunity to work alongside medical teams and dietitians, which I really enjoyed.

How did you pivot from that work to opening your own practice?

About two years ago, I got this itch that I needed to do something different – even though I had no idea what that was at the time. I think it came from a lot of places. From some major burnout in what I was doing, not necessarily related to the work itself – though the work itself contributes when you're in a helping profession. You give so much of yourself, especially working with such high-acuity issues.

At that point in my career, I was traveling the country every other week and had three young kids at home. Going back and forth between South Carolina, California, and Ohio – those states were my territory for the treatment centers I was overseeing. I was very burnt out by traveling, and I had gotten away from clinical work. I was pretty much exclusively directing these centers, which is somewhat clinical – ensuring that the clinical services were up to par – but I wasn’t really hands on with patients anymore. I don't think I even realized how much I missed that until I started doing it again.

Every time I had the urge to find certainty, I would force myself to sit with the uncertainty.

I started thinking about, “What does the next piece look like?” I’ve always had some entrepreneurial spirit, but I never really considered myself as having the right temperament to be an entrepreneur. Mostly because I thought entrepreneurs had to be really capable of taking big risks, and I'm very risk averse – or I thought I was very risk averse. I think I saw myself in a particular way, like, “I operate best in a really tight structure and taking direction.” But I was always a really, really good manager of people and director of people, so I knew I was skilled in doing that part.

I was so burnt out at that point that it was really hard to envision doing something different because I had been operating from a place of nothingness. There wasn't any room left for creativity. I finally got to a point where I realized I couldn’t figure out what the next step was from this place of total burnout. I needed to just pick something and do it, so I could get out of the mental space I was in. So, two summers ago, I went into private practice as a therapist. It took a while for a lot of reasons, but I started my practice, and I was finally in this space where I was able to think and dream.

Tell us more about what you were dreaming.

I thought, if I'm going to start a practice, there are two goals. During my corporate healthcare career, I was constantly seeking out coaching opportunities. How can I be a better leader? How can I manage my team better? How do I develop the skills that comprise good leadership? Within my medium-sized organization, none of that was really available unless you were a senior-level executive.

It felt like all those resources about how to be a better leader came, essentially, once those people already were leaders and, honestly, once they were screwing up; focusing on how we can improve this situation or whatever. So that was something I was interested in trying to address, as someone who was really passionate about cultivating female leaders. Initially I was thinking more about women leaders in business environments, but then I began to really expand that definition of leadership within our communities at lots of different levels.

I was also still really interested and passionate about mental health in the more traditional sense. I had lots of conversations with my husband about how I really wanted to do two very different things, and I wasn’t sure how they intersected. I started to think more about the intersection of those two things: How do we support women's mental health as a way to really empower them to step into the roles they’re meant to occupy?

A lot of the things that had traditionally been thought of as barriers for women – you know, being confident enough, and so on and so forth – had often been framed as a problem with the individual instead of the system. But in my background – working with systems and individuals, but particularly with individuals – I was thinking about how to address the barriers the system imposes and support a woman’s mental well-being. In the conversation around women's leadership, we’re often focused on how do we empower them, empower them, empower them. We never really take an internal look at their emotional well-being through that process and what that means.

Because I was afraid I would come at it with too much of a therapist’s lens, I did some women's leadership training and coaching. It was really interesting because it was all psychology, just repackaged. I was like, “Oh, I know what that is… I know what that is – it's just repackaged in a different way. This is all psychological science.” So that made me think about: How do we make mental health resources accessible to women in ways that might feel less stigmatizing? Or less "I have to wait until I'm having a clinically relevant situation or diagnosis before I reach out for support"?

So, that's the backdrop. When I started the actual practice a year and a half ago, it was just me. Then I hired someone else, and someone else, and now we have two more psychologists starting in two weeks. Soon there will be five of us locally who are part of this team. And I have two staff members who are remote – one in California and one in Virginia – who do work for their local areas.

How would you describe Galia Collaborative’s mission?

I like to think about what we do as women's mental health work, but through a social justice and empowerment lens. Our mission is to support women's mental health, so they can elevate their impact. We're not opposed to seeing men, but we rarely do. [Laughs.] For some reason, they just don't come to us.

What we do falls in a few buckets. We do individual therapy with particular emphasis around more common women's mental health concerns. We do individual coaching for women instead of general life coaching. It's more focused on leadership and leadership development.

We offer Circles, which are small groups of women who share a common issue – like prenatal anxiety, binge eating, being a healthcare practice owner – and want to support each other through it. We consider Circles more coaching oriented, so it’s not a therapy group, but kind of a small mastermind that runs from anywhere from four weeks to six months in duration.

We also do workshops. We've done our own workshops internally, and we've done some corporate workshops about the intersection of mental health and women's leadership. Eventually I want to create more digital resources that are accessible on demand and at a lower price point, to make services more accessible for a wider range of people.

Your foundation of intersectional feminism and social justice is such a cool approach. Tell us more about why Galia Collaborative is founded on those principles.

On a personal level, I feel fortunate that I grew up in a really feminist household. From the time I was 7 years old, my mom was helping me write letters to game manufacturers about the fact that boys always won the board games in TV commercials; what was that about? She taught me to really question the status quo. So I feel really appreciative that that curious, questioning nature was facilitated in me.

I went to graduate school for clinical psychology – but I applied to both women's studies and psychology Ph.D. programs. Even as I was applying, I knew they were very different – obviously with some overlap, but very different in terms of the path. I was like, I don't know, I guess I'll just decide which to take if I get in anywhere.

I was always pulled in these two directions as if they were very different – which they are in the sense that psychology’s historical roots are so patriarchal, white, and capitalist in terms of how we've gotten the theories and the research. Most of the research we have on how the human brain works is based on young, white, fit men.

I was so burnt out at that point that it was really hard to envision doing something different because I had been operating from a place of nothingness.

Psychology tends to be so individualistic. It really centers the problem in the person in a way that other fields – like social work and counseling – don't do as much. They're more apt to think about the system, or what could be driving the problem outside of the individual. Psychology struggles to take a more holistic or systems-level approach to think about what the cultural influences are that precipitate mental illness, for example. So, when we see clinically significant mental illness, we ask how does the environment, or access to healthcare, or access to education play a role? How is the brain responding to trauma? When we think about things like P.T.S.D., we think, “Is there an acute stressor? Did you witness something or go through something?” Instead of looking at it more holistically: How did your experience growing up in an impoverished environment contribute to your brain changing? Even the experience of oppression causes trauma and that changes the brain.

When I started my therapy practice, I wanted to make it very clear that the problem is not always within the individual. It's not always a matter of will power, or that you're not trying hard enough if you continue to struggle with something. And I think that is a slightly different definition of empowerment. Sometimes empowerment is letting someone know that you're in a really dysfunctional system, and it makes total sense you're reacting in this way; what can we do about that? Instead of saying, “You're failing because you need therapy to think differently about the situation.” You don't need to think differently about the fact you're being treated like shit! [Laughs.]

On your website, it says you're a "self-acknowledged recovering perfectionist." How do your own experiences and personal growth play into your practice?

In every way, always. Even developing my practice, the whole adventure of starting and building it has been a challenge to my perfectionistic nature. I saw myself as a perfectionist because I really liked order, structure, knowing what to expect, what I was going to do next, and planning ahead. But, really, what I think perfectionism is all about… it’s often a response to trauma or to a chaotic system. Perfectionism at its core provides us a sense of safety. Like, if I know what to do and can control this little square of my world, then everything is going to be fine, and I can kind of regulate myself.

When I started building this business, I very intentionally didn't map out even a one-year plan, which felt really counterintuitive to me. [Laughs.] It just felt so uncomfortable; I had taken M.B.A. courses, and it was the opposite of everything you learn. But I also trusted myself, and trusted the process enough so that every time I had the urge to find certainty, I would force myself to sit with the uncertainty. Because I also knew I didn't know exactly what I wanted it to look like, and I was still recovering from burnout. So if I made a plan, it would be coming from this place of seeking certainty because I was recovering from burnout instead of what I really wanted this to look like.

I made that first year an opportunity for things to evolve organically – and that's very privileged, I want to acknowledge. I was privileged to do that because I knew I had confidence in myself, and I knew people would be referring clients to me because I had good relationships, so it would be okay if I didn't have it all mapped out. I could give myself a chance to figure it out. And fortunately, that worked well, and the economy was right, and all of that.

I feel like this endeavor has been a practice in recovering from my own perfectionism. It's been so helpful for me just on a personal level – tuning into intuition and what feels right, even if I can't always verbalize it.

That really hits close to home. Even with the pandemic right now – I'm a planner, and now all that control I thought I had is gone, which I know a lot of other people are also feeling. There’s an interesting article about "that feeling you're feeling? That's grief." It talks about grieving the life you knew and the plans you had and all that. As a psychologist, can you talk some more on that?

I think it comes down to acknowledging the losses that are inherent in this. Thinking about, like, what are all the things we're kind of losing right now? Of course, it's social connection and events that have been planned and things like that. But I almost feel that on a very existential level, we're also losing the illusion of safety; that we're kind of untouchable. To some degree, society is like, "We can get through anything" and that’s very much an American ideal, too. Even if we're skeptical or critical of American idealism, I think on some level we've really internalized – most of us, I should say – the strength of America is to overcome. And now we’re witnessing these failures everywhere.

When I started my therapy practice, I wanted to make it very clear that the problem is not always within the individual.

For me, personally, there's a lot of grief and – this is where I'll be really psychologisty – I feel like we all have a time in our lives when we realize our parents can't protect us from everything. For some people, that's very, very young, especially if they grow up in an abusive or traumatic household. And for some people, they're really old when they realize, "Oh, my parents are really fallible and they can't protect me from everything." I always listen for that when I talk to people because it tells me a lot about them and the way they've constructed their world.

So this [pandemic] feels like a trigger to that in some ways. Like, we're actually not safe and no one can really protect us – from the illness itself or the economic impact. We're all at the mercy of the world right now, and that's like the ultimate anxiety. Plus, we’re grieving that sense of security we feel we’ve lost. It's a privilege to have had that security; I know not everybody experiences that security but for many of us, we do, so that is such a loss right now.

When someone realizes they need help – whether it be coaching or mental health services or what have you – what would your advice be if they're unsure about where to start?

What's interesting, particularly about mental health, is that with most services in the world, we rely on word of mouth. You know, referrals and asking friends. But because of the stigma that's still associated with getting help, some people don't want to ask around or ask their friends or post on Facebook looking for recommendations. But I love when people do ask people they know about who they trust or who they might know. That's both helping them get help and combatting that stigma itself and really normalizing it.

In terms of mental health support, Psychology Today is probably the biggest resource for people to connect with a provider in their area, just because it's so broad based and providers from everywhere are listed there. I also tell people that if they feel comfortable, a lot of people still find help via their primary care doctor, if they have one. People can ask them for recommendations.

Right now [during the stay-at-home orders], it's actually a great time to reach out – because of what people are going through, of course, and because a lot of mental health providers have time right now, given that caseloads have completely changed and pretty much everybody is doing everything through telehealth. I know so many people who have run into calling ten different providers and none of them having space, but that's not nearly as true right now.

Who's an influential woman in your life?

This is me being a perfectionist; I want to get the right answer for myself. It’s cliché but I'll say my grandmother, who my daughter is named after. She's a very special person in my life. When I mentioned before growing up in a very feminist household... My mom had me before she was married, so we lived with my grandma for a period of time. She had a part in raising me, so she was influential in that way, for sure. She was sort of the matriarch of that sense of feminism I grew up with, even though it had to be very subversive for her. On the surface, she was very traditional, you know, a Catholic housewife raising six kids and all of that. And now she's quite outspoken, which is really cool.

Thanks so much to Ashley and Galia Collaborative for their support of Women of Cincy. For more information on sponsorships, contact Chelsie Walter.